Week 9: Japanimation II

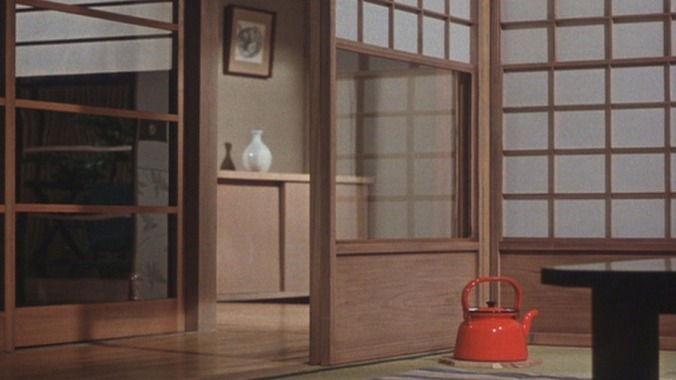

The Unforgettable Kettle shot from Ozu’s first colour film Equinox Flower, 1958

There are obvious differences between Anime and Western animation. The stylistic differences as well as the content/narrative differences are easy to pick up by even the most passive of viewers. But what about something that is much subtler, something that has seeped into Anime films and has been a quintessential element of Japanese film-making ever since its introduction by the acclaimed director, Yasujiro Ozu in Tokyo Story, 1953.

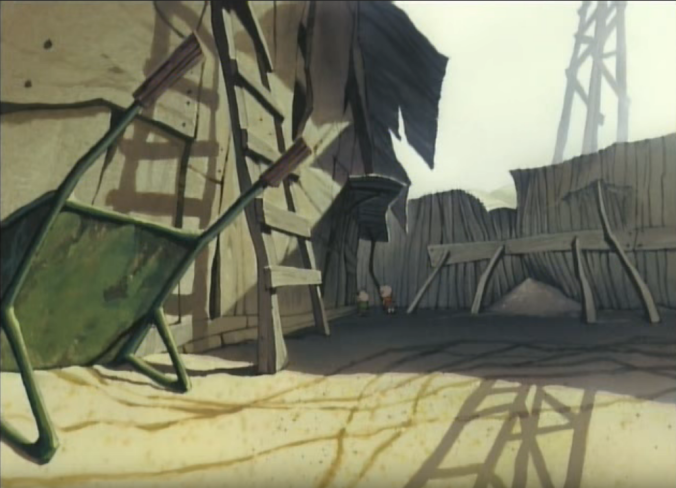

Grave of the Fireflies, 1988

It’s the pillow shot.

From My Neighbor Totoro, 1988

Have you ever noticed how two characters in an Anime are interacting with each other in some way, whether it be fighting, arguing, or conversing, for plot or narrative reasons and as they finish up their impromptu session, the shot cuts away to something that is completely still and completely different?

Princess Mononoke, 1997

That is the pillow shot.

The entire three minute sequence from Ghost in the Shell, 1995 in the middle of the film acts as a form of elongated punctuation

It’s derived from traditional Japanese Poetry, a technique called the pillow-word, and this specific technique is one of the defining characteristics of Japanese Cinema as well as Anime, especially films by Miyazaki and others since the 1980s.

Even in a high action, sci-fi movie like Akira, 1988, pillow shots are littered through the film

Technique wise, it is a cutaway from the previous scene to some other visual element, not necessarily beautiful, or brilliantly drawn, or animated to be magical/fantastical; it can be as simple as a chair, a room corner, or a cow eating grass, and as the shot holds, for few seconds or more, the camera cuts back to the characters/plot again.

And more recently, The Red Turtle, 2016

The pillow shot interrupts the narrative, by injecting a sense of calm and quiet, some might even argue a form of silence; at minimum the shot slows the pacing down even if it doesn’t need to be.

Again from Grave of the Fireflies, 1988; the film is famous for its use of pillow shots

But do not mistake this for a transitional shot because by no means is this technique used as a bridge between one scene and another. Nor is it an establishing shot, since nothing needs to be established between the previous scene and the next.

Miss Kobayashi’s Dragon Maid, 2017

Frankly they can be completely removed from the film itself and most viewers will not possibly notice. But that is how you lose, as mentioned earlier, a quintessential part of what makes Anime, so Japanese and so different from Western animation.

An inconsequential moment where nothing happens in The tale of Princes Kaguya, 2013

It’s punctuation in a sentence, hitting the breaks in an Anime film, so it stands right at the border between narrative and non-narrative cinema. It doesn’t further the story, or plot, or advance character motivations, but it’s still there on screen.

There are even brief pillow shots in an anime series like Dragon Ball Super, 2015-present

The pillow shot gives audiences a chance to breathe, to ponder what just happened between the last scene and wonder what will happen going forward. If the active viewer notices this shot, then it offers a whole new level of appreciation that the passive viewer will not fully grasp and comprehend. Since Japanese Animators are willing to go through all that trouble to animate inconsequential moments for no other reason than a simple “let’s take a break for a few seconds,” then we as viewers, should admire their craft.

There are lots of pillow shots in Your Name, 2016 of urban architecture such as streetlamps, skyscrapers, and power cables

The luxury of unmotivated moments in animation is wholly and quintessentially Japanese and the pillow shot is one of the most common techniques deployed in the majority of Anime films, that most audiences will never be aware enough to notice.

This scene in Grave of the Fireflies, opens with a pillow shot, has one in between, and ends with a pillow shot.

Sources:

Roger Ebert on Grave of the Fireflies

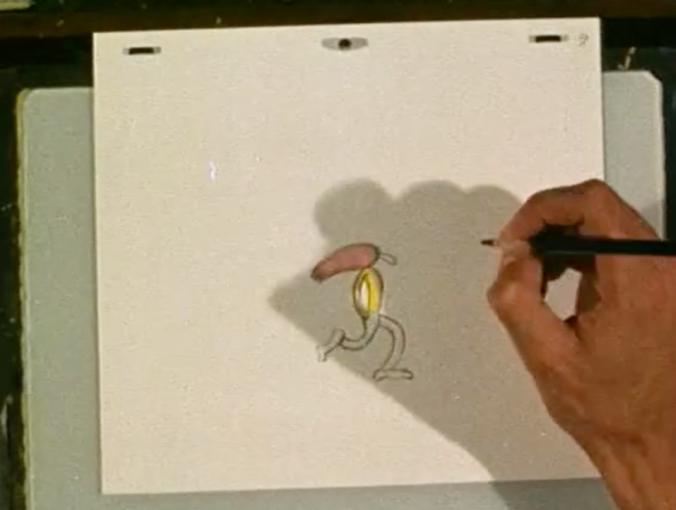

The animators hand makes repeated appearances to influence all the different manners of animation, from claymation to cell animation to direct film carving.

The animators hand makes repeated appearances to influence all the different manners of animation, from claymation to cell animation to direct film carving.